Yesterday my daughter asked me, “What’s a mortgage, and why won’t people be able to pay them?” While I always enjoy discussing personal finance, this was not the kind of question I was expecting from my 11-year-old. Why was a fifth grader asking about mortgage defaults? The answer: She heard about it when the news was on last night.

We are living in an unprecedented time right now. The increase in coronavirus cases in the United States has many states and school districts across the country closing schools for an extended period of time. My state, Pennsylvania, just cancelled state testing for this school year. All of this has raised a lot of questions and has parents and educators trying to determine the best way to help students while they’re not in school.

Parents are stressed, teachers are stressed, and policy makers are stressed. Knowing how stressful the unknown is for adults, imagine what our students are facing. Adults want to keep things as normal as possible while students are not in school, but life is anything but normal right now.

There are so many great resources available online and I’ve seen wonderful ideas from both educators and parents about how to fill a child’s day from beginning to end. While all these efforts are fantastic, I wonder if some of our kids would benefit from a little less “structure” and a little more self-directed learning.

There’s been so much talk over the last few years about maker spaces, Genius Hours, and other activities where students have more control over their learning. Is this the perfect time – while “school” is so up in the air – to let students choose what their learning will look like for even an hour a day or maybe an entire day?

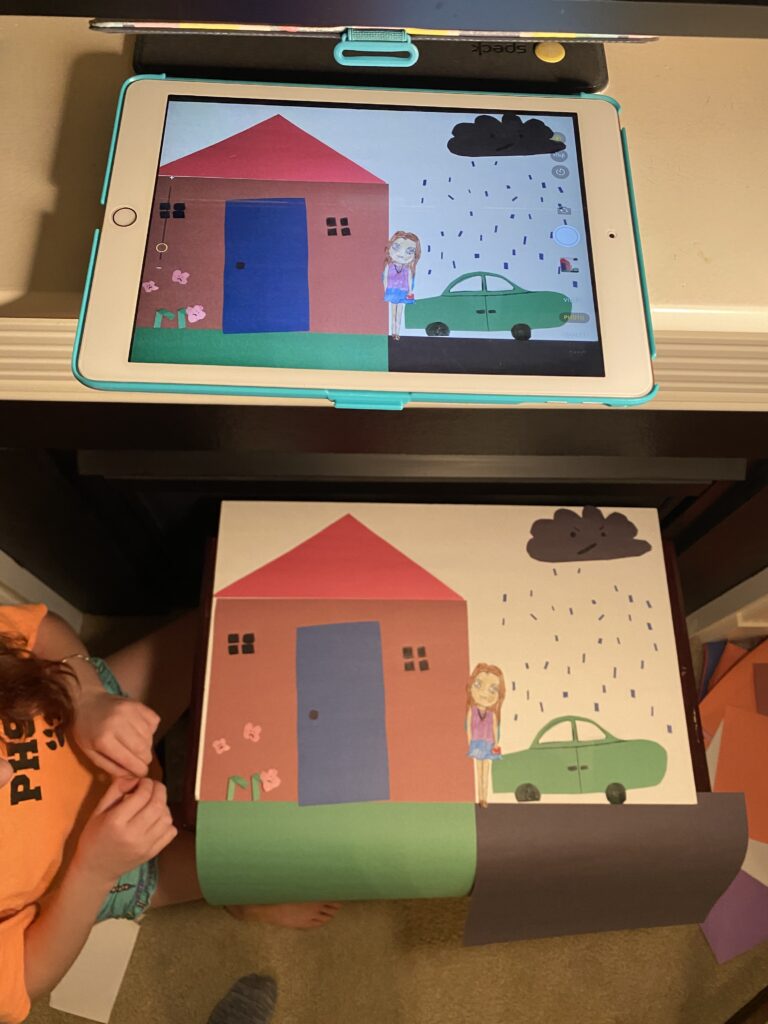

When my daughter asked me about mortgage defaults, I realized we needed to take a step back and let her be a curious kid for the day. I wanted her to try and forget about all the uncertainty happening outside our house. Instead of the math, ELA, and science lessons we’ve done the last few days, today we explored an interest she’s had for a couple months – stop motion animation. We found some videos online, downloaded a recommended app, and spent the entire afternoon, and some of the evening, creating stop motion animation movies.

As we worked on her project, Anna realized pretty quickly that this was challenging work. She had to learn how to use the new app, develop a storyline, create all the visual elements, and solve problems along the way. We did not talk about factors and products, compare the theme of two stories, or determine the impact humans have had on ecosystems. And for today, that was okay, and I think it was just what she needed. In fact, I think it’s what more of our kids need right now.